What makes good climate policy?

Researchers in the CERES project conducted a study comparing fifteen hundred climate policy measures from forty-one countries. Their aim was to identify which actions bring about a significant reduction in emissions, and the findings from their groundbreaking study were recently published in top-tier journal Science.

Regulations, subsidies, taxes: in recent decades, countries across the globe have introduced numerous and various climate protection measures—but identifying which policies actually bring about the desired results isn’t always straightforward. Now, however, researchers in the WSS-funded CERES project have published a study comparing and evaluating fifteen hundred climate policy measures that have been enacted over the past twenty-five years in no less than forty-one countries on six different continents. The measures concern the building industry as well as the electricity, industrial and transport sectors.

The study is the largest ever to be based on established statistical methods, says main author Nicolas Koch from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) and the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change (MCC) in Berlin, and adds: “We worked with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and were able to draw on data that had not yet been published.” The study findings were presented in a recent article (*) in Science, one of the world’s most prestigious academic journals.

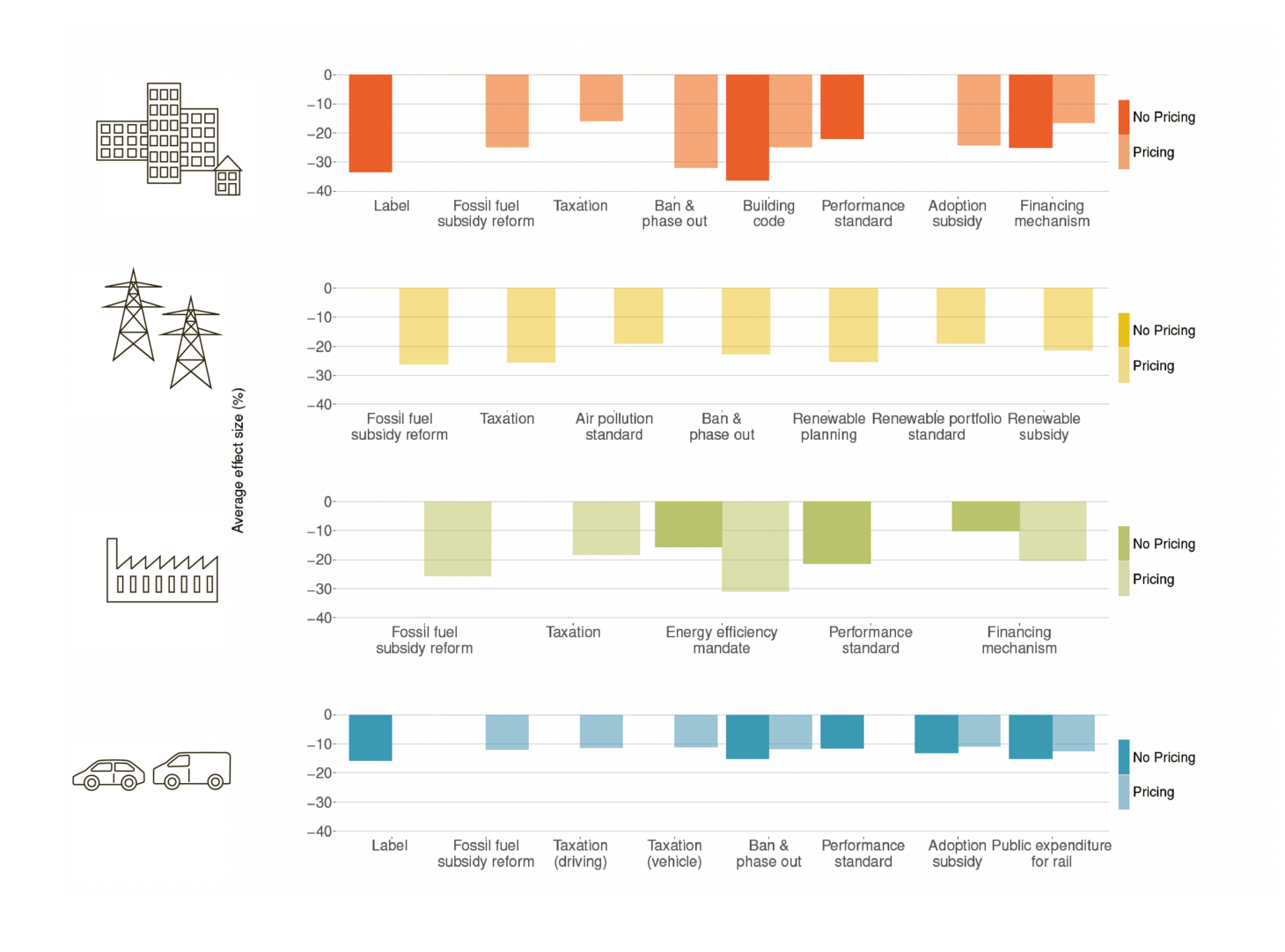

Measures that brought about emission reductions of at least five percent were the focus of the study. The team discovered that, in the past two decades, only sixty-three cases met even this bar. “At first sight, that’s fairly discouraging, and it indicates that governments often have no other option than to just try out random climate protection measures due to a general lack of evidence about what strategies actually work,” as Koch relates. However, he also says that further analysis of the successful measures reveals how powerful well-crafted climate policy can actually be. Indeed, effective policy packages reduced targeted emissions by nineteen percent on average. Some—like the mix of instruments in the UK’s electricity sector—achieved a reduction of forty to fifty percent within just a few years.

Policy mix the ideal solution

One feature shared by all sixty-three success stories is that several measures were introduced at the same time. “It’s not enough to rely on subsidies, for example, or on regulations alone,” Koch explains. “What’s needed is a combination with price-based instruments such as carbon and energy taxes.” Bans on coal-fired power plants and combustion car engines provide an interesting example, as the researchers were unable to identify a single case in which a ban alone led to a meaningful reduction in emissions. This was attained only in tandem with taxes or price incentives.

Nicolas Koch says the electricity sector in the UK is a prime example of a successful policy mix: “In the British government, policy makers set a minimum carbon price that was much higher than the prices traded at the time.” This decision was then combined with a government programme to foster renewable energies and a clear timetable for phasing out coal-fired power generation, which is particularly detrimental to the environment.

Different approaches are found in the US—where emissions in the transportation sector were reduced through a three-pronged approach of tax incentives, subsidies for low-emitting vehicles, and CO2 efficiency standards—and Sweden, which achieved reductions in the building sector thanks to a mix of carbon pricing and subsidy programmes for building renovations and the replacement of heating systems. “These examples show that governments have to be prepared to introduce climate protection packages that also include price incentives and taxes,” Koch explains.

Different instruments for developing countries

In addition to climate policy measures in industrialised countries, the study also examined climate action in developing and emerging countries. Koch says that only a few studies on these regions have been conducted—which is problematic, as measures can have very different outcomes in industrialised and developing countries. In the electricity sector, for example, the researchers discovered no impact of pricing instruments in developing countries.

Koch believes this is because the electricity markets in these countries are set up very differently to those in the industrialised world. If there’s only one governmental electricity supplier, and if the electricity and energy prices are regulated by the state, it’s possible that carbon pricing will fail to develop its desired market effect. “In these countries we tend to see positive trends stemming from subsidies and regulations such as renewable portfolio standards,” Koch says.

Processing the enormous amounts of data in such studies demands sophisticated tools; for the CERES study, the researchers further developed existing statistical methods using machine learning. Nicolas Koch says the new analysis infrastructure is also suitable for other applications and can be made available to the wider research community on request.

Closing the evidence gap

The study authors hope their work will help close the evidence gap on the effectiveness of climate policy measures. To be sure, measures enacted in one country will not necessarily translate one-to-one to another country, but successful policy packages in states with similar structures can nevertheless provide a useful basis for shaping policy. The researchers also developed an interactive web tool where all sixty-three effective policy interventions can be explored in detail. The tool is designed for decision-makers such as those responsible for climate protection measures in governmental offices. The project has generated interest, and Koch says the first queries have been received.

At the same time, the Potsdam researchers have already begun focusing on other aspects of climate policy: new technologies for example are instrumental in reducing emissions. “That’s why our next step will be to look at policy measures that effectively foster green patents and technologies.”

In addition to climate change, the team in the CERES project also address issues surrounding overuse and the protection of other global public resources. “One example is biodiversity, which is a major public good,” Koch explains. “But when it comes to what constitutes good biodiversity protection policy, we’re still basically stumbling around in the dark.” For better or for worse, the researchers won’t be running out of work any time soon.