News

Brilliant development

A microchip that is 100 times smaller and 100 times more energy efficient—this is the stated goal of the research team at the Centre of Atomic Scale Technologies, which has received funding from the Werner Siemens Foundation since 2017. Already after a short year’s work, the ambitious goal no longer seems utopian. On the contrary.

Despite his passion for physics, and despite having won numerous distinctions for his work, ETH professor Jürg Leuthold never ceases to be amazed by what he discovers: “As soon as we think we’ve reached the limits of physics, we learn that a great deal more is possible.” It wasn’t too long ago that Leuthold was certain that microchips simply couldn’t be made any more minuscule. At some point, when the chips used in cell phones or coffee machines become too small, they begin to lose efficiency. But then Leuthold, an experienced photonics researcher, made a revolutionary discovery: instead of functioning via electrons, the microchips of the future will work on the single-atom level or via ions. “This means they’ll function much the same way our brains do,” says Leuthold. What’s more, the new microchips are proving much more efficient than conventional microchips. And the fact that computers lose energy in the form of heat is a sign that there is still untapped potential to optimise the technology. “The human brain can process a lot more without requiring a cool-down phase,” says Leuthold.

Jürg Leuthold is professor at ETH Zurich, where he heads the Institute of Electromagnetic Fields. Together with Professor Thomas Schimmel of the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology and Professor Mathieu Luisier from ETH Zurich, he is working on quite literally revolutionising the semiconductor industry. In particular, the researchers are developing a new kind of microchip: one that is 100 times smaller and 100 times more energy efficient—and able to at least match the current speed of data processing. To support these innovations, the Werner Siemens Foundation financed the establishment of the Centre of Atomic Scale Technologies in 2017.

Energy efficiency exceeds expectations

In 2018, Jürg Leuthold once again had good reason to be amazed: the tests conducted by the Karlsruhe group pushed the limits of what researchers generally believed physically possible. “Until quite recently, we thought a single switch would need 40 to 50 millivolts of energy,” Leuthold says. “In the tests under lab conditions, however, six millivolts were already enough.” This means that the microchip of the future would not be just 100 times, but up to 10 000 times more energy efficient. To be sure, a long road lies ahead before theory is put into practice. But the results show that it is absolutely possible to imagine the microchip of tomorrow in entirely new dimensions—thanks to single-atom technology. When the project began, the researchers gave themselves until 2021 to develop an initial processor with 20 components, and until 2025 to build more complex processors. Not quite one year later, Leuthold still thinks the ambitious schedule is realistic, saying the team has not only made major progress in the area of energy efficiency but also regarding speed. Moreover, the technology has become increasingly reliable.

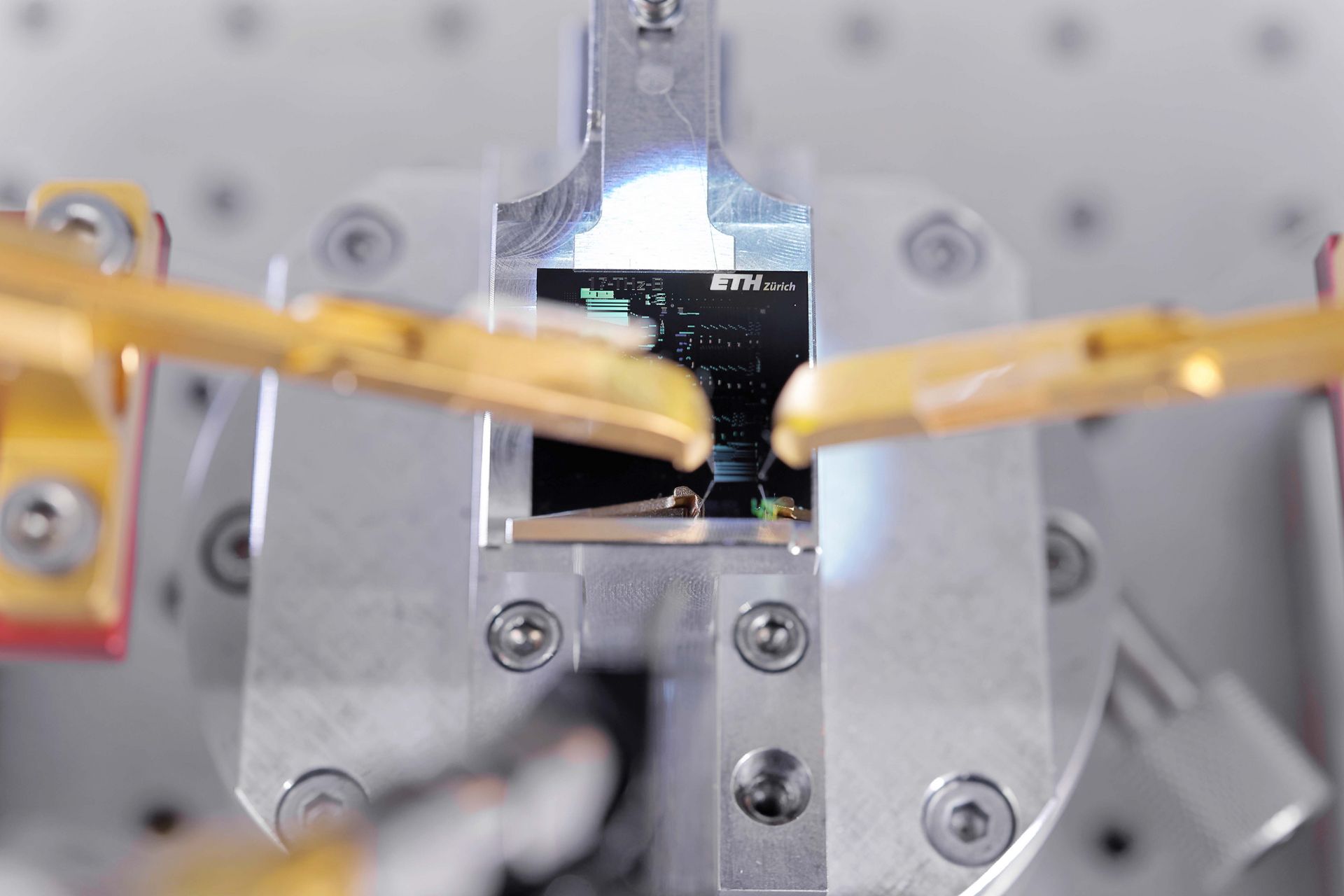

First digital photodetector

The ETH research team is currently building the various components necessary for the tiny single-atom switches, which measure only a few nanometres. Already last year, they succeeded in developing a modulator that takes an electrical signal and converts it into an optical (light) signal. Now they have also presented the counterpart to the modulator: a photodetector. And not just any photodetector, but the smallest that has ever been built—and the first digital photodetector, full stop. But Leuthold is not yet satisfied. “There’s still room to optimise energy efficiency.” The next step is to develop what is probably the most important component for the single-atom switch: the transistor, which is a type of on-off switch. Some day, billions of these transistors will be built into microchips—which is why both minimising size and maximising energy efficiency are so critical. Another goal for the coming year is to create the memory component that stores information. In the meantime, 10 specialists in the fields of electrotechnology, materials science and engineering, and fundamental physics are working on the project, and four more will soon join the team. The researchers regularly publish their findings in renowned journals. And they are reaping the benefits: it is no rare occasion that respected researchers travel long distances to visit the centre and gain first-hand information. Jürg Leuthold is delighted: “For us, it’s a sign that our project is gaining more and more exposure.”

Text: Andres Eberhard

Photo: Felix Wey