Ueli Angst and his fascination for corrosion in concrete

When asked about his qualities as a scientist, civil engineer and ETH professor Ueli Angst answers: “I’m not your typical researcher who’s always lived and breathed academia.”

After completing his studies as a civil engineer, Ueli Angst worked more than five years in industry, including a stint at the advisory firm Swiss Society for Corrosion Protection (SGK), where he now acts as honorary president. His experience in consulting at SGK lent him deep insights into the real problems facing concrete structures and helped him form lasting ties to industrial practice. At the same time, Ueli Angst is equally knowledgeable about theoretical considerations on how concrete manufacture could be made more sustainable—which led to his appointment as assistant professor at ETH Zurich in 2017. “My aim is to unite theory and practice,” he says.

Angst is particularly motivated by the fact that improving concrete manufacture is a key way to tackle climate change and conserve natural resources. “Modern infrastructure is quite literally the pillar of our prosperity,” he says. “Without it, we could never transport goods and move people the way we do. The big topics of sustainability and prosperity are virtually embedded in a nation’s infrastructure.”

A new look at concrete

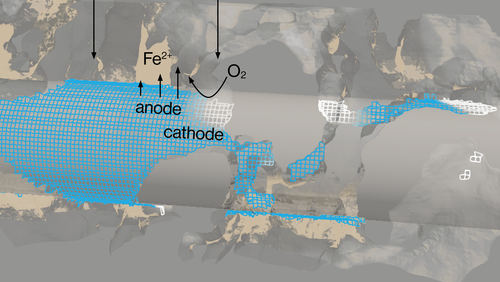

Our knowledge about concrete has changed drastically over the past fifty years, Angst explains. Up until around the middle of the last century, it was believed that reinforced concrete structures were built to last forever. Then came the realisation that they, too, are subject to corrosion—but that highly alkaline concrete can prevent decay. Starting in the 1980s, engineers began almost solely relying on alkalinity levels in concrete, with standards and textbooks being adapted to reflect this new approach. “At the time, it was most certainly the right thing to do to prevent corrosion,” as Angst says. “And one consequence is that we build much more durable structures than we did before.”

Indeed, when Angst began studying corrosion fifteen years ago, the issue of sustainability was not yet foregrounded. “Back then, I didn’t make a connection between corrosion and climate change,” he admits. It was only over time that he understood how the dogma of high alkalinity in concrete had become a problem for the climate.

The right place

Today, Angst says, European countries are leading the way in calls for sustainable concrete manufacture. “But up to now, concrete itself has been the focus, not corrosion processes.” Ueli Angst believes that Switzerland in particular is an ideal place for his research. In addition to the country’s long-established cement industry, sustainability is a burning issue in Swiss society. And to conduct his interdisciplinary research, Angst has access to top-notch infrastructure and outstanding specialists in related fields at ETH Zurich, EPFL, the Paul Scherrer Institute and Empa.

Ueli Angst believes the construction industry must take action on climate change, saying there are scores of ideas on how concrete can be manufactured more sustainably. He adds: “By studying corrosion, I want to draw attention to another aspect critical to the manufacture of climate-friendly and durable concrete structures. Science and industry have a responsibility to address this issue.”

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/d/f/csm_01_WSS_News_Beton_90d32370a8.jpg)