Benefactors with an eye to the future

The founding capital of the Werner Siemens Foundation was donated by members of the Siemens family. After Charlotte and Marie—the daughters of Carl von Siemens—set up the Foundation in 1923, their cousins Anna and Hertha von Siemens as well as their brother’s wife, Eleonore (Nora) Füssli, contributed significant funds. That much is clear, but otherwise very little is known about the original benefactors of the Foundation. Now, however, new publications are shedding light on the lives of the Siemens women.

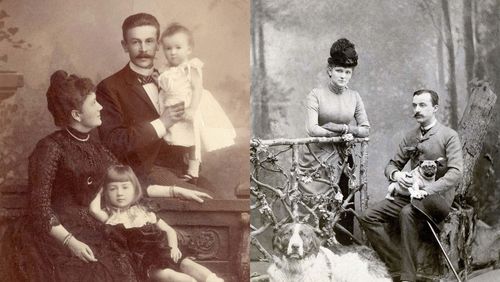

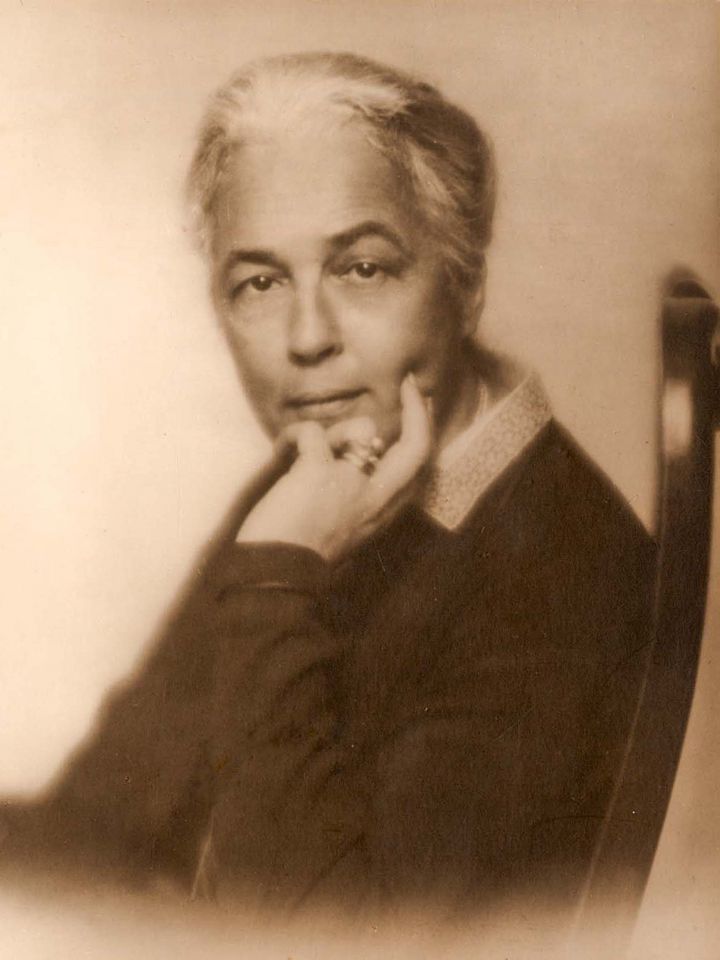

Two authors—Béatrice Busjan and Yvonne Gross—are researching the lives and works of the Foundation benefactors on behalf of the Werner Siemens Foundation. Béatrice Busjan is a historian and art historian. Author and media specialist (libraries/archives) Yvonne Gross co-authored a book about Eleonore (Nora) Füssli, published in 2018, with Ludwig Scheidegger, the former director of Siemens Switzerland. Because Nora Füssli (1874–1941) was the last Siemens woman to donate to the Foundation, her life will be portrayed in the 2020 report; this edition introduces the first benefactors of the Foundation, Anna (1858–1939) and Hertha (1870–1939), both daughters of Werner von Siemens. Yvonne Gross and Béatrice Busjan are currently writing the life stories of the two women. In the following conversation, we discuss their work.

Béatrice Busjan and Yvonne Gross, can you tell us why Anna and Hertha decided to donate a considerable amount of money to the Werner Siemens Foundation?

Yvonne Gross: Anna and Hertha were very close to their cousins Charlotte and Marie von Siemens, who set up the Foundation in 1923. After their traumatic experiences in post-revolutionary Russia and being forced to flee their homes, Charlotte and Marie were absolutely determined to provide for future generations of the Siemens family. Anna and Hertha shared this wish.

Béatrice Busjan: Like Charlotte and Marie, Anna and Hertha had a strong sense of family loyalty, but because they had no children, they focused their care-giving energies on their nieces and nephews. The two women also lived through the period of German hyperinflation in the 1920s, and after being widowed at a young age, they were naturally concerned about their own financial security and looked for ways to put their inheritance to good use. That is, in brief, the background of their donations to the Werner Siemens Foundation.

What did you know about Anna and Hertha before you began researching the two women?

Yvonne Gross: I knew that Anna was the oldest daughter of Werner von Siemens and that Hertha was the youngest. Anna married the paper manufacturer Richard Zanders in Bergisch Gladbach, and Hertha married the chemist Carl Dietrich Harries in Berlin. Neither woman had children. From my earlier research, I also knew about Hertha’s great interest in art.

Béatrice Busjan: Anna’s name has mainly been linked with the “garden city” estate in Bergisch Gladbach that she and her husband built for employees at the Zanders paper factory and that she continued to develop after Richard’s death. Hertha, on the other hand, was known for her commitment to social issues within the Siemens company. But it was difficult to say much about their personalities and characters because, until now, no one had conducted serious research into their lives.

What discoveries about Anna and Hertha surprised you the most?

Béatrice Busjan: Hertha’s close ties to the artistic and scholarly avant-garde of the early 20th century and her discerning tastes. Future Nobel Prize winners were frequent guests at her home, and she recognised the high quality of works by artists like Vincent van Gogh and Bruno Taut years before this became the general consensus.

Yvonne Gross: Anna’s contemporaries describe her as very determined and well able to get her way. Now we’ve just discovered that, early on, she was coached by an experienced politician who gave her decisive tips. And just looking at her schedule from the year she died shows how much she still planned to do!

Béatrice Busjan: It’s also very admirable how Anna and Hertha dealt with personal misfortune and the social upheaval of the day, and how they were always ready to begin anew.

Was it difficult to find information about the women?

Béatrice Busjan: When reading available scholarly literature or contemporary sources like newspapers, it becomes readily apparent that the two women often “disappeared” behind their husbands, meaning that activities attributed to their husbands may have been initiated by Anna or Hertha. This is, of course, typical of the historical era we’re dealing with: the second half of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. That’s why it’s important to read the contemporary sources against the grain and always question who was actually driving a decision. It was also clear from the start that studying source materials would be essential for a well-documented narrative of the women’s lives. So we collected birth and death certificates, baptism records, purchase and share-holding contracts as well as private and business-related documents and correspondence.

Yvonne Gross: These documents are still in possession of the family or stored in public archives. The available sources haven’t always been analysed by previous scholars, and in some cases they hadn’t even been indexed yet, which was the case with the correspondence between Anna and her godson Werner Ferdinand von Siemens and her letters to her aunt Anne Gordon. Many a time we were the first people in 80 to 100 years to even look at these sources. In such cases, the first job is sorting and deciphering a lot of handwriting.

Where did you find the most information on Anna and Hertha?

Yvonne Gross: Most material stems from the Siemens Historical Institute, where we found many more documents on the two women than we had anticipated when starting our work. When clarifying individual questions, we contacted numerous other archives: the university archives in Berlin and Jena, the city archives of Bergisch Gladbach and Cologne, and the archives of the German states of Lower Saxony and North Rhine-Westphalia. When researching Hertha, we had to conduct searches in Italy, and we discovered quite a bit about Anna in America. In addition, the descendants of the von Siemens, Zanders, Harries and Eckener families also provided key information.

Béatrice Busjan: The letters their father, Werner von Siemens, exchanged with his brothers, especially his correspondence with Carl von Siemens, are an excellent source for the first part of the women’s lives. The letters between Werner and Carl are also extremely touching, because the brothers weren’t just business partners in an international company, they were also very caring parents who were in constant contact regarding the welfare of their children. This correspondence naturally ended with the death of Werner von Siemens in 1892, but afterwards, the letters Anna and Hertha wrote to their relatives also provide a great deal of information. Yet we found the best source to be the letters the sisters wrote to each other. In this setting, the two are “alone”, and they tell each other things that otherwise remained unsaid. For example, Hertha smuggled champagne into a clinic where she was receiving treatment, and Anna was considering uprooting her entire life to support her godson Werner Ferdinand.

Interview: Brigitt Blöchlinger

Photos: Siemens Historical Institute, Berlin; Yvonne Gross, Berlin

Publications

The life stories of Anna von Siemens and Hertha von Siemens, edited by the Werner Siemens Foundation, will be published at the end of 2020 by Thomas Helms Verlag, Schwerin.

Authors

Béatrice Busjan, MA, historian and art historian, director of the agency Geschichte + Kunst in Hamburg

Yvonne Gross, research specialist, media and information services in Berlin

Book on Eleonore (Nora) Füssli

Yvonne Gross and Ludwig Scheidegger: Nora Füssli, edited by the Werner Siemens Foundation,

Thomas Helms Verlag, Schwerin, 2018