Daring darlings

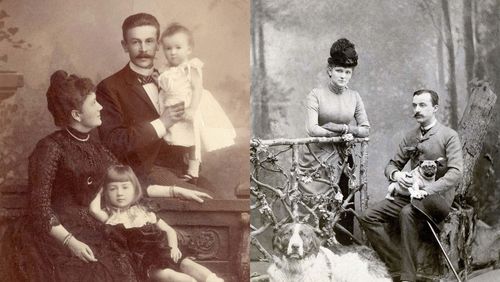

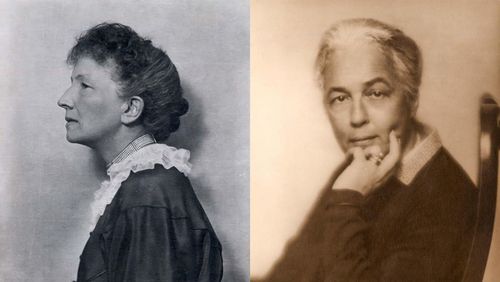

In recent years, several works exploring the history of the Werner Siemens Foundation have seen publication, including the 2020 double biography of Anna and Hertha Siemens, two of the Foundation’s benefactors. Although Anna and Hertha led very different lives, the half-sisters remained close and, in 1931, they decided to bequeath the greater part of their substantial fortunes to the Werner Siemens Foundation.

Anna and Hertha Siemens were half-sisters; their father was industrialist Werner Siemens. Their childhoods, however, were strikingly different. When Anna was just six years old, her mother, Mathilde Drumann, died. Anna and her three siblings often had to do without their beloved father for weeks, as Werner Siemens was focused on establishing his firm, Siemens & Halske, and frequently away on business. By contrast, Hertha, twelve years Anna’s junior, was the first child of Werner and his second wife, Antonie Siemens. At the time of Hertha’s birth, Siemens & Halske was running smoothly and fifty-four-year-old Werner Siemens felt free to spend more time with his family—and quite literally stargaze with his youngest daughter.

Unlike sisters

The half-sisters were also decidedly different in character. Already as a child, Anna was called headstrong, resolute and somewhat shy, whereas Hertha was a peacemaker, good-natured and idealistic. In their married lives, the women were also separated by geographical distance: Anna wed the paper manufacturer Richard Zanders in 1887, and the couple settled in Bergisch Gladbach in Rhineland; Hertha married the chemistry professor Carl Dietrich Harries in 1899 and moved with him first to Kiel, then Berlin. But the two women also had much in common. In particular, they shared a deep love for their father and the large, far-flung Siemens family. And neither woman had children.

Beloved father

Werner Siemens was a devoted family man who cultivated a strong sense of community. Gregarious by nature, he often invited the families of his siblings and friends to spend weeks at his Charlottenburg estate in Berlin. This is how Anna and Hertha became close to their aunts, uncles and cousins from a young age. “My little children are thriving,” Werner wrote to his sister-in-law in London in 1861. “Willi and Anna in particular are blossoming like young roses [...]. All the cousins spent nearly the entire day together and made a right lively, high-spirited little troupe.” 1

Before her death, Werner’s wife Mathilde looked after Anna and her other children during his long business trips. She wrote frequent letters to her husband, enclosing photographs of the “darlings, our treasures”.2 Indeed, the frequent correspondence in the Siemens family was a major source of information for Anna and Hertha’s biographers.

Early loss of mother

But Anna’s happy early childhood was overshadowed by serious illness. She herself nearly succumbed to diphtheria, and her mother died of tuberculosis in 1865. It was a loss that left a deep mark on six-year-old Anna. Werner looked on in concern as his oldest daughter grew more and more reserved. He tried to offer fatherly advice: “Once you have understood that Christian love is the driving force that ennobles and blesses humanity [...], your heart will soften and be open to love, and this will make love grow yet more powerful.” 3 But Anna continued down her own path, which was only partly in line with prevailing ideas of how a refined young lady should conduct herself.

1 Béatrice Busjan and Yvonne Gross: Anna Siemens und Hertha Siemens. Published by the Werner Siemens Foundation,

Thomas Helms Verlag, Schwerin, 2020, p. 14.

2 Busjan/Gross, 2020, p. 19.

3 Busjan/Gross, 2020, p. 32.

Werner Siemens’s second marriage

In 1869, Werner Siemens fell in love with Antonie Siemens, a distant relative from Hohenheim in southern Germany, and the couple married. Although Werner had hoped that Anna would welcome his second wife as a new mother, Anna refused point blank—despite her great love for her father. Yet not all was difficult, and young Anna also knew happier moments, filled with both carefree and notable experiences. When she was eleven years old, she was invited to the children’s ball at the royal court. And when she was fifteen, her parents entrusted her with the demanding task of supervising construction work on the Charlottenburg villa during their absence. Werner sent her instructions from Ireland—letters that also reported on the dramatic difficulties of laying the transatlantic telegraph cable between Ireland and North America.

Half-sister Hertha

Born in 1870, Werner Siemens’s youngest daughter, Hertha, had a much more harmonious childhood. In addition to her birthplace of Berlin Charlottenburg, she also had a home in Hohenheim in southern Germany, where her mother was from. She spent her summer holidays with her grandparents at the Hohenheim castle, making the acquaintance of university rectors, agricultural scientists, botanists, chemistry professors and future Nobel Prize laureate and discoverer of X-rays, Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen—and all their families.

Researchers as friends

At home in Charlottenburg, Werner Siemen’s circle of friends also included scientists, giving young Hertha further opportunities to learn about the world of research; she was interested in physics and mathematics but also in painting. At the time, however, women were not allowed to study at university or at an art academy. It was only thanks to her father’s active support that Hertha could attend some courses.

With Anna’s marriage in 1887, all of Hertha’s older half-siblings had left home. Hertha felt a little lonely and, as her father put it, sought to “bring some youthful life to the home”. 4 But in reality, the old father and teenage daughter very much enjoyed their time together. They conducted experiments in the private lab at Charlottenburg and carried out studies in astronomy.

Travels with her parents

In 1890, Werner Siemens decided to visit Kedabeg and Kalakent in the Caucasus, where he and his brother Carl owned a copper mine. “Papa always acts as though it’s impossible to take a young girl on such a journey. I’m waiting patiently to see what rules they’ll impose on me,” Hertha wrote to Anna.5 Her patience paid off, as the adventurous trip taken by the small family turned out to be an unforgettable experience. “If there’s such a thing as reincarnation, I was certainly once one of these half or entirely wild creatures that galloped through life on horseback. When things get downright crazy, I always feel right at home and very much alive,” Hertha wrote from Baku.6

Werner’s death

Werner Siemens spent more time with his youngest daughter than with any of his other children. They had the same inquisitive mind and shared a desire to understand the world in great detail. Hertha lived with her mother and father up to her marriage, and she took advantage of the privileges offered in her family home, becoming intimate with her parents’ circle of friends and acquaintances. She acquired a natural ease at moving in the world, much like her father. This served her well when Werner Siemens died in 1892, at the age of seventy-six. Hertha was able to look forward and, despite being only twenty-two years old, claimed she felt like “a complete and rational human being with an opinion worthy of respect”.7

4 Busjan/Gross, 2020, p. 126.

5 Busjan/Gross, 2020, p. 131.

6 Busjan/Gross, 2020, p. 133.

7 Busjan/Gross, 2020, p. 139.

A paper manufacturer and a chemistry professor

Both Hertha and Anna married for love, and both women actively supported their husbands’ careers. Thanks to the extensive networks and the financial security the sisters brought into their marriages, many a difficult situation was mastered. However, neither sister was spared misfortune: Hertha’s child, born on 11 November 1900, survived only fourteen hours, and Anna’s husband was killed in a tragic gun accident in 1906. The fact that Anna and Hertha had no children may partly account for their lifelong commitment to philanthropic causes.

Philanthropic work

In 1909, Hertha established the Hertha von Siemens Foundation, whose mission was to enable employees and managers at the Siemens factories to take affordable holidays in Bad Harzburg. Hertha also looked after affairs at the Siemens children’s home and had the Siemensstadt day-care facilities enlarged. She also used her understanding of art to purchase works by as-yet unknown artists, including an autumn landscape by Vincent van Gogh, which she bought in 1905 when the Dutch artist was still highly controversial.

Anna was instrumental in developing an avant-garde housing project that she initiated with her husband in 1897 and maintained after his death. The “Gronauer Wald” project was designed as a single-family housing estate near the forest, and all strata of society were welcome to move in—from working-class families to company managers. The project was a success, and by 1937, five hundred and twenty houses had been constructed. In addition to her philanthropic work, Anna was committed to fostering close ties among the large Siemens family. She worked with forty-nine of her relatives to set up a family foundation. And she worked tirelessly to buy the house in Goslar that had belonged to the first known member of the Siemens family, later converting the building into a museum.

War and inflation

The Siemens family was impacted by the hyperinflation that raged through Germany in the aftermath of World War I. In December of 1918, Hertha took on the delicate task of showing Anna the economic difficulties facing both the Siemens factories and the family finances.

Their experience of inflation and currency reform—not to mention the fact that Communist Russia had expropriated and expelled their cousins Charlotte and Marie—led Hertha and Anna to consider how they should best safeguard their assets. In 1926, the two women (both of whom were widowed by this time) agreed to sell their Siemens & Halske shares to the Mira Treuhandgesellschaft AG (a trust company) in Schaffhausen, Switzerland. They had the purchase price paid out in annual instalments, and the balance earned interest at Mira, thus providing Anna and Hertha with a secure income.

Generous benefactors

Five years later, in 1931, Anna and Hertha transferred their Mira assets (roughly 1.4 million Swiss francs) to the Werner Foundation established by their cousins Charlotte and Marie in 1923; the Foundation also assumed Mira’s other duties. In their wills, both women stipulated that the rest of their assets would go to the Werner Foundation, with the aim of ensuring long-term benefits for the descendants of Werner and Carl von Siemens. It was also around this time that the sisters changed the name of the Werner Foundation to the Werner Siemens Foundation.8

On 19 December 1938, Anna celebrated her eightieth birthday. Her younger sisters and brother—Hertha, Käthe and Carl Friedrich—surprised her with a visit. It would be the last time that Werner Siemens’s oldest and youngest daughter would meet: Hertha died the following January, and Anna in July of 1939. As though the two sisters had even agreed on the year of their death.

8 Busjan/Gross, 2020, p. 194.

Text: Brigitt Blöchlinger

Photos: Siemens Historical Institute