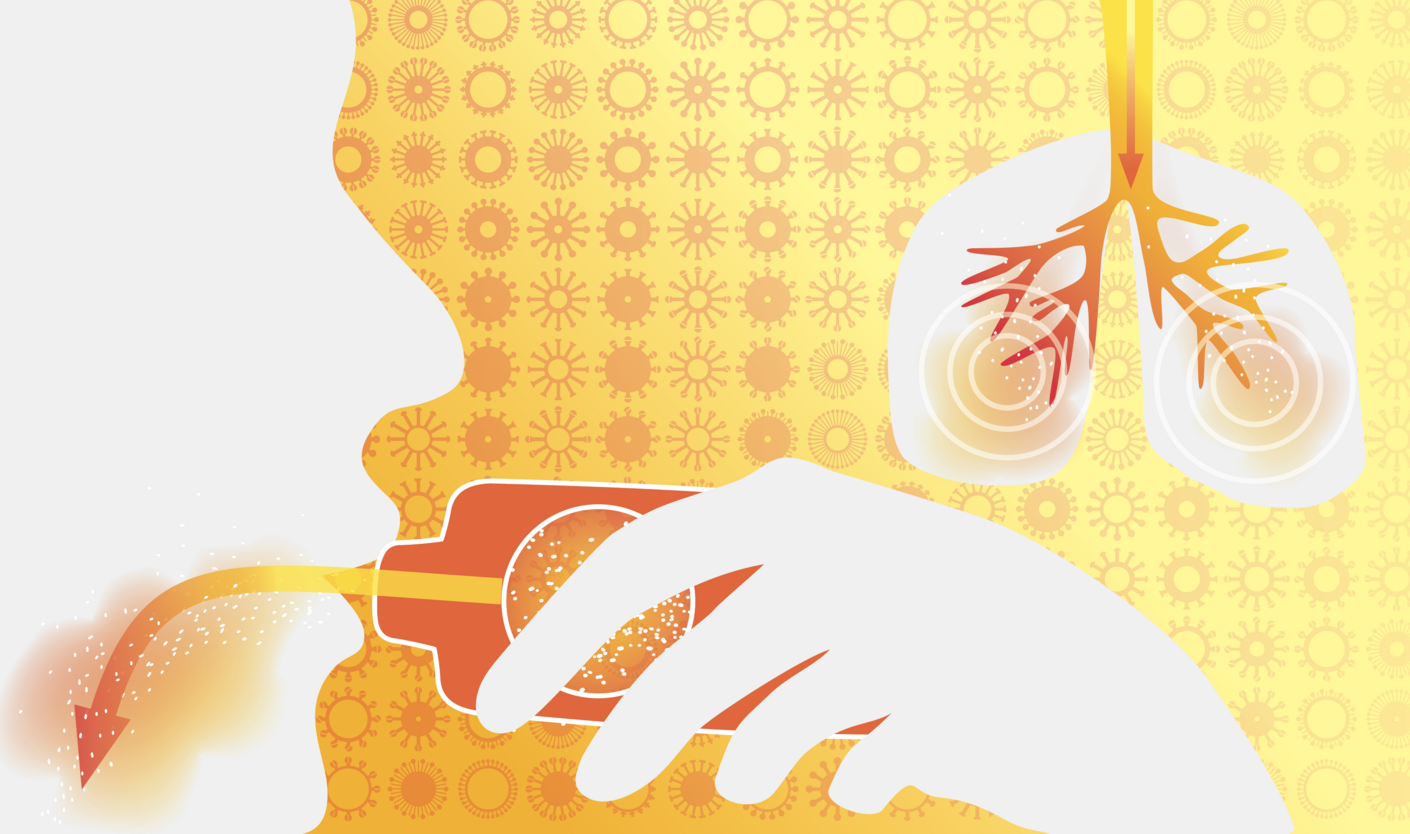

A spray to neutralise viruses

Last year, Francesco Stellacci and his team at École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) continued working on their novel antiviral agents that could one day be used to treat a wide range of viral infections. The researchers have now transformed their agents into an inhalable powder form—meaning the future antiviral drug will be easy to administer as a nose spray.

At the EPFL Supramolecular Nano-Materials and Interfaces Laboratory, a team led by Francesco Stellacci are currently focusing their efforts on developing a drug to treat viruses that cause respiratory tract infections. This includes the common respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) that, while relatively harmless for most people, can cause serious infections in infants and the elderly. However, the innovative antiviral drug designed by Stellacci and his team can do more than combat RSV—and now the drug’s potency has been confirmed in two animal experiments conducted in 2023: a SARs-CoV-2 study with hamsters and an influenza study with ferrets.

The new antiviral belongs to the class of so-called entry inhibitors, which are drugs that prevent viruses from entering a host cell, thus robbing them of the ability to reproduce and spread. In the case of RSV, it also ensures that a virus can’t make its way through the nose or mouth to the respiratory track—and damage the lungs. The antiviral created by Stellacci’s research group is a broad-spectrum entry inhibitor whose “backbone” has been combined with the chemical compound mercapto-undecane sulfonic acid (MUS). MUS is capable of neutralising a wide range of viruses: it irreversibly inactivates them by occupying protein parts in a virus via a sophisticated binding mechanism.

Powerful powder

On the basis of the positive results in the preclinical trials, the researchers dried the agent to attain a substance that can be used in a conventional dry-powder inhaler. The substance was found to be both effective and well tolerated by the test animals. The researchers’ long-term aim is to make an antiviral that can be easily administered as a nose spray.

Francesco Stellacci says it takes years to develop new drugs. The antiviral substance is subjected to strict controls not only in terms of efficacy but also regarding its toxicity. Currently, a Dutch contract research organisation is testing to see how many viruses are still living in the lungs of the lab animals after administering the drug—the fewer, the better, of course—and whether the chemical compound harms the animals’ lungs. “The viruses already damage lung tissue. We can’t have our medication causing even more problems,” Stellacci explains, adding that “no observable side effects” were evident in the first preclinical trial with mice. He’s confident that his innovative antiviral drug will also prove to be well tolerated in future preclinical studies: “So far, the trial data are very good.”

Only perfect is good enough

To conduct in vivo studies on toxicity levels in the MUS compound, the molecules need to be produced in large (industrial-size) quantities, and current global good manufacturing practices (GMP) must be upheld. At present, experts at EPFL are working with Francesco Stellacci to prepare the necessary documents and contracts for the trials.

Last year, Stellacci was also busy drafting a proposal for an international centre for viral research at EPFL. The idea is to create a space that promotes dialogue and enables international research groups to consolidate their efforts in combating viruses of all kinds. “Basically, it would be about finding which agents are effective at combatting viruses,” is how Francesco Stellacci describes the centre’s mission. As soon as he submits the detailed proposal, the Werner Siemens Foundation will carefully review it and consider funding the centre.