Archaeologist of the invisible

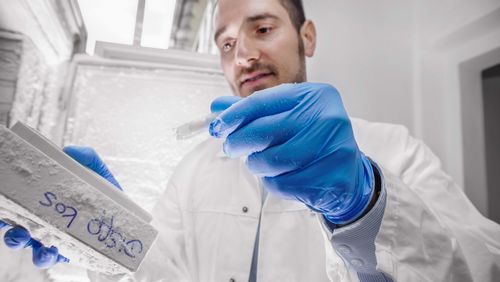

Bones and ancient tools from early human settlements have never captured the interest of archaeologist Christina Warinner—her passion is bacteria. She wants to demonstrate the crucial role microbes played in human evolution. And to explain why we should show them a little more respect.

At home, Christina Warinner has two cats and a dog. “And millions of other pets,” she says with a laugh. Because her research is so closely tied to the innumerable bacteria that inhabit our bodies, she has begun seeing them as a kind of house pet. “We really don’t appreciate what these bacteria do for us,” says the archaeologist. “Of course, some microbes make us ill, but for tens of thousands of years, they have also been helping humans stay healthy.” Nevertheless, the field of medicine has only just begun to research the microbiome — the entire community of microorganisms in the human body—and Warinner’s work helps to shed light on how the microbiome has evolved. And although archaeology has traditionally focused on uncovering the remains of ancient civilisations, she is fascinated by prehistoric microbes—what she calls an “archaeology of the invisible”. Her particular fascination is DNA found in ancient dental plaque, and when giving presentations on her work, she jokes with her audience and suggests they refrain from brushing their teeth so that future archaeologists have plenty of material to work with.

Undeterred, innovative

That researching ancient dental plaque would become her profession was hardly preordained. Christina Warinner grew up in the Midwest of the US, in Kansas, where she was mainly encouraged to do sports. But Warinner was drawn more to reading science books of all kinds, and her many interests made it difficult to settle on a major at university. In the end, she studied microbiology and archaeology, and she discovered her true vocation in uniting the natural sciences and the field of archaeology. After earning her PhD at Harvard, Warinner took on a postdoctoral position at the University of Zurich, where she was the world’s first researcher to examine the microbiome in the mouths of prehistoric humans; her main focus was analysing the remains of DNA found in dental plaque. Looking back, Warinner says that “a lot of my peers thought I was crazy and said I would never find DNA, that it would have decayed long ago”. But Warinner was not to be deterred—and found what she was looking for. Using traces of DNA and proteins from the microbiome, she was even able to reconstruct when and where humans began dairy farming.

Curious, dedicated

Nevertheless, many other questions remain unanswered, and Warinner says we “still don’t have a good understanding of what the microbiome does”. We do, however, know that the microbiome of modern humans in Europe and North America is significantly less diverse than that in nonindustrialised societies. This is presumably due to changes in diet and hygiene in addition to the wide use of antibiotics. Christina Warinner wants to combine archaeological methods with state-of-the-art technology to discover what the human microbiome looked like in pre-industrial times. For her work, she commutes between two universities and two continents: she is professor at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena and at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. At the Max Planck Institute, Warinner found a kindred spirit in Pierre Stallforth: “ We’re both enthusiastic about our work, and we’re ready to explore new paths.”

Text: Adrian Ritter

Photos: Felix Wey