Dental calculus on Easter Island

Microbial DNA preserved in the dental calculus of ancient humans is proving increasingly valuable, and now, in a recent publication, a team led by Christina Warinner describe how they applied the method to investigate the history of human migration in Oceania and Island Southeast Asia.

The settlement of Oceania, a mosaic of islands stretching across the Pacific Ocean, occurred in several waves over the course of millennia, when peoples from Southeast Asia arrived at new island groups, often within short periods of time. To reconstruct the history of these migrations, researchers generally study genetic material found in human bones and teeth. But because DNA quickly degrades in tropical heat and humidity, the method often meets with limited success.

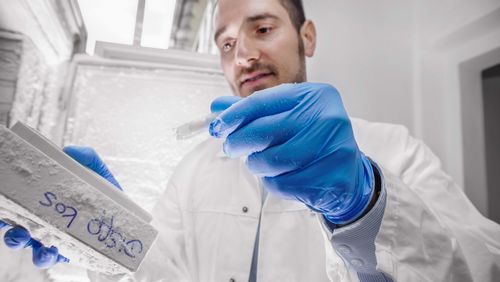

Now, however, a research team led by molecular archaeologist Christina Warinner is exploring an innovative approach for studying past human migrations in Oceania: using ancient DNA, they reconstructed the genomes of oral bacteria trapped in the dental calculus—calcified dental plaque—of skeletal remains found at archaeological sites on eleven islands, including Vanuatu, Fiji, and Easter Island. For the study published in Nature Communications (1), the researchers sequenced the oral microbiome of 102 humans spanning a period of roughly 3000 years.

Earlier studies on the settlement of islands in Oceania and Southeast Asia have revealed surprising patterns, says Warinner, professor at Harvard University and co-leader of the palaeobiotechnology project, which receives funding from the Werner Siemens Foundation. “Genetic studies indicate that a later wave of settlers largely replaced the first populations on the islands. At the same time, however, linguistic analyses suggest that the newcomers adopted the languages of the earliest inhabitants.”

Well-preserved genetic material

Warinner believes the oral microbiome could provide new information about the interrelationship between genetic and cultural heritage. “The microbiome can reveal much more than information related to genetic ancestry,” she explains. “It also provides clues about cultural interactions—social relations and family ties, how relatives were cared for.” This is why she wanted to confirm whether the method of analysing dental calculus is fundamentally capable of detecting relevant traces.

And in fact, the study generated several key results. One finding is that in challenging tropical and subtropical environments dental calculus seems to preserve ancient DNA in archaeological specimens surprisingly well, indeed much better than bones. The researchers extracted high-quality genetic material from roughly 70 percent of the dental calculus samples. By contrast, in earlier studies of ancient DNA found in bones from the same region – many from the same individuals – just under three percent of all samples contained more than five percent endogenous genetic material. The stability of DNA in dental calculus even in the warm and humid tropics is unexpected. “It highlights the potential of dental calculus as a source of valuable archaeological information,” Christina Warinner says.

The oral microbiome of ancient humans in Oceania is distinctive compared to that found previously on the mainland in Europe, Asia and Africa. “It’s not completely different, but we’ve discovered several bacterial species there that either have yet to be described or are no longer found elsewhere,” Warinner says. Comparing the bacterial strains—the genetic variance between individual species—was revealing. “While the strains on different islands were distinct, the strains within people on same island were very similar,” she explains. “This hints at cultural practices, such as food and beverage sharing, that may have contributed to the predominance of a particular strain on each island.”

Next aim: unknown species

This pattern can occur when bacteria have a high rate of circulation within a population. Warinner says this makes sense in the case of oral bacteria on a small island: “Communal beverages, such as kava, play a key role in social gatherings and ceremonies in the Pacific, and their preparation and consumption can lead to the sharing of oral bacteria.” Such traditional practices may have contributed to the development of a distinct microbial pattern on each island.

The researchers also identified several bacterial species that could make it possible to reconstruct how the islands were populated. “But we have more work to do there,” Warinner says, mainly because some of the species have rarely been studied. “One of the reasons we know so little about them is that these species aren’t associated with disease—rather, they’re present in healthy oral plaque.” In a follow-up study, Warinner’s team are now analysing these microbial species by reconstructing their genomes from scratch.

The aim of a second follow-up study is to provide a global overview of current knowledge on the oral microbiome. “We’re compiling all data that have been published so far from all time periods. It’s a massive dataset,” Warinner says. The data comprise information from archaeological finds—including those in the Oceania study—but also dental calculus genomes from modern humans, in addition to all the data Warinner and her research group collected from Indigenous communities in Cameroon.

Meticulous care with data

This exacting work has also given rise to another recent publication (2), as Warinner relates. “When we began collating data for the project, we realised that the way many studies have archived their data in databases is surprisingly inconsistent, which makes it much harder to use the information for further research.” To remedy this, the researchers launched a series of initiatives to create standardized processes and checklists to facilitate uploading better and more complete data.

“This work caught the eye of the editors at Nature,” Warinner explains. “They invited us to write an article about the problem and to present our solutions.” She says one issue is that the data have not always been recorded with care, as seen when incorrect sequencing methods are reported. “These errors can often be identified and corrected, even if it involves a lot of effort,” Warinner says.

Another problem, however, has more serious consequences. “A lot of researchers don’t upload all their data,” Warinner says. Because microbes are ubiquitous, microbial DNA is also found when human or animal remains are examined. In some cases, only 10 percent of a sample is human DNA, while over 90 percent stems from microbes. “Researchers who are interested only in human or animal genetic material often think the microbial DNA is irrelevant and simply throw it out,” Warinner explains.

This must be prevented at all costs—because the genetic material of these microorganisms is highly valuable. They’re like miniature time machines enabling researchers to travel far back into the past, a fact not least demonstrated by the groundbreaking research carried out by Christina Warinner and her colleagues in the WSS palaeobiotechnology project.