Prehistoric medicine

Is the future of medicine a journey to the past? In their palaeobiotechnology project, biotechnologist Pierre Stallforth and archaeologist Christina Warinner are taking an unusual approach to solving the problem of life-threatening antibiotic resistance: they’re analysing the dental plaque of early humans for substances that can be used to combat resistant bacteria strains of today.

Antibiotic resistant bacteria are believed to be one of the greatest threats to human health, and researchers from all over the world are frantically seeking new medicines. The team working on the palaeobiotechnology project in Jena, Germany, has the same aim, but they’re looking in a surprising place: in 100,000-year-old dental plaque found in the remains of early humans.

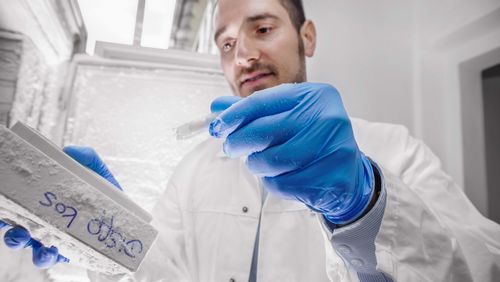

Teeth are treasure troves for anthropologists. They’re so hard that they remain preserved in the ground for millennia – better than any other part of the skeleton. What’s more, food scraps and bacteria are conserved in dental plaque. It’s the latter that the team in the palaeobiotechnology project plan to use to find new antibiotics. The potential is great because bacteria have always produced antibiotic substances – to ward off food competitors, for example. The great advantage to prehistoric antibiotics is that they no longer occur in nature, and modern-day bacterial strains haven’t had the chance to develop defence mechanisms.

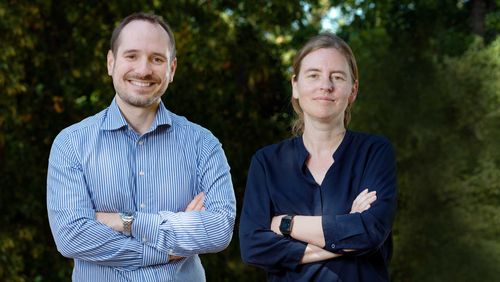

Archaeologist Christina Warinner from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Jena is responsible for analysing the dental plaque. Her lab has collected thousands of archaeological specimens, some of which are up to one hundred thousand years old. When Warinner and her team identify genetic material that is potentially responsible for producing antibiotic natural products, they send the samples on to the lab of their colleague Pierre Stallforth, chemist and biotechnologist at the Leibniz Institute for Natural Product Research and Infection Biology, also in Jena.

There, he and his team introduce the DNA sequences into the genome of present-day bacteria. In steel tanks, the bacteria are grown, multiplied and stimulated to produce prehistoric antibiotic substances. The final step is testing the agents directly on multi-resistant pathogens. At present, several promising candidates are undergoing analysis in Pierre Stallforth’s lab.

Facts and figures

Project

Researchers at the Leibniz Institute for Natural Product Research and Infection Biology – Hans Knöll Institute and theMax Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Jena are examining prehistoric DNA for natural products that can be used to develop new antibiotic drugs.

Support

The Werner Siemens Foundation is supporting the establishment of the new research discipline of palaeobiotechnology in Jena, including a professorship, two postdoctoral positions, seven PhD students, two technical assistants and research infrastructure.

Funding from the Werner Siemens Foundation

10 million euros

Project duration

2020 to 2029

Project leader

Dr Pierre Stallforth, group leader of Chemistry of Microbial Communication at the Leibniz Institute for Natural Product Research and Infection Biology – Hans Knöll Institute in Jena

Academic partner

Prof. Dr Christina Warinner, group leader of Microbiome Sciences at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Jena and professor at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts